Gray Fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus)

Abstract: The purpose of conducting this research was to discover to what extent Sonoran desert mammals were affected by an urban development that took place within the midst of their natural habitat. This was accomplished by comparing data that was collected before and after construction began. In 2012, a Bushnell trail camera was set up within a neighborhood next to a wash that animals commonly use as a travel corridor. Trail cameras are devices that are triggered via a motion sensor to remotely take pictures. During that year, javelinas, foxes, raccoons, coyotes, bobcats, and rabbits were photographed. In 2015, after construction began on a 15.14 acre piece of land within the subdivision, the same camera trap was again set up next to the wash. After analyses of the data were conducted, the results revealed that while the foxes and javelinas were affected the most (considering their drastic decline in numbers and tendency to pass through the neighborhood less frequently), the coyotes, bobcats, raccoons, and rabbits were not quite as impacted. This may be explained by the fact that while javelinas need large areas to live and forage (considering their large herd sizes), other species may still survive and adapt in the midst of human intrusion into their natural habitats. Coyotes, bobcats, and raccoons also still had potential prey items. In addition, rabbits don’t need much space. The fox, however, appeared to mostly leave the region altogether. Ultimately, my research landed me at both the regional (SARSEF) and state (AzSEF) science fairs, where I received numerous awards and recognitions.

Coyote (Canis latrans)

When I received my first camera trap in the spring of 2012 and started collecting random data with it, I never thought how far I’d go with all those images and videos. However, this research project that I will be describing here is the perfect example of just why it is so critical to not throw away data that seems to serve no purpose at the time of its collection (note: to learn more about how camera trapping works, see my post, “Camera Trapping: Learning the Basics”).

Javelina Mother with Young (Pecari tajacu tajacu)

The study area in which this project took place was in my neighborhood. There are several small washes that run throughout the subdivision, connecting neighboring pieces of land. One of them runs right by my house; the camera was strapped to a tree located on the upper bank of this wash. Additionally, animals use these washes as corridors to get from one natural piece of land to another. These paths (approximately 30 feet wide), the upper bank, and surrounding area also contain various trees and plants, including mesquites, palo verdes, creosote bushes, saguaro cacti, prickly pears, chollas, Texas sage bushes, barrel cacti, ocotillos, agaves, hedgehog cacti, fishhook cacti, and different types of grasses. Although I’d set the camera up in this location next to my home shortly after I had received it, I have since lost that assortment of spring/summer data. This highlights how critically important it is to save files in more than one location. Nonetheless, what I will be focusing on in this page are images and videos that I collected in the fall/winter during my freshman year in high school.

Raccoons (Procyon lotor)

My Bushnell Trophy Cam model was set up on September 20, 2012 and taken down on January 2 of the following year. It used eight alkaline AA batteries and was on photo mode throughout September to mid-November. When triggered, three consecutive infrared pictures were taken in a row with an interval of three seconds before the next set of photographs could be taken. Then from the rest of November to December, the camera was on video mode. The length was mostly 20 seconds, though a few were either shorter or longer as a result of determining what the most efficient length was. As for how often I collected the images from the two gigabyte SD card, I would typically go out about once a week, though occasionally I’d also look on a daily basis simply out of curiosity. Moreover, it is worth noting that I occasionally utilized bait to draw the animals in. This primarily consisted of the raw parts of a store-bought turkey that weren’t used in cooking, as well as any meat leftovers that weren’t consumed. I also once tried laying a shiny, crumpled piece of tin foil covered in perfume on the ground in front of the device to see if any species would be attracted to it. As a side note, though, I seriously question whether I should continue employing these tactics in the future (not to mention it is HIGHLY discouraged to feed wildlife as they can imprint on humans).

While the Fox Seemed to Appreciate the Sweet-Smelling Foil…

…the Coyotes made good use of the Leftover Turkey. Oddly Enough, the Javelinas ate the Cooked Turkey too!

When 2013 rolled around, I wasn’t certain about what to do with all of my images/recordings. However, this is when a proposal came through in my neighborhood by a developer (Sabino Canyon Road Properties) to rezone a 15.14 acre piece of land approximately 500 feet away from my home. 130 three-bedroom rental units, named “Avilla” homes, have since been built there. This land, located on the northeast corner of N. Sabino Canyon Road and E. Cloud Road in the Catalina Foothills Subregion, was the last larger piece of natural habitat remaining in the surrounding area of Sabino Creek. Prior to construction, several public hearings were held where opponents of the proposed development plan voiced their opinions. One was held July 31, 2013, and another on September 17, 2013. Pictures of the wildlife in the area were shown at these hearings, including images of species rarely seen during the day from my camera photos. In spite of strong opposition from the public, though, the request of the developer of Pima County to rezone the land was approved on May 6, 2014 after another public hearing and a 4-1 vote on behalf of the Board of Supervisors. Construction began shortly after. The lot, which was originally zoned at LIU 3.0 (Low Intensity Urban), was rezoned at MIU 8.6 residences per acre (Medium Intensity Urban).

Satellite Image from Google Maps Showing the Land Prior to Construction. The Circle is where my House is Located

Beginning Stages of Construction

Completed Units

After these rental apartments had been built, I started to wonder what kind of an effect this would have had on the wildlife in my neighborhood. Thus, in 2015, I decided to explore this topic further as a senior in high school by collecting more data and then comparing it with that which I had already previously gathered. My mentor for the project was Dr. Melanie Culver, a professor in the School of Natural Resources and the Environment at the University of Arizona. I also worked with her database manager, Susan Malusa. Originally, I conducted research and gathered more data in the summer of 2015 using my own camera and two others that were lent to me by Dr. Culver. Below is a photograph of where the devices were set up next to my house, along with their detection range, in both 2012 and 2015. However, because I was principally interested in comparing winter data with winter data to get more accurate results, I collected more images in the winter of 2015 as well. This was primarily what I used in my comparisons from before and after the development was built. Thus, I will be mostly focusing on those results here and won’t be discussing the summer 2015 data any further. Additionally, I once again utilized only one camera (my own Bushnell model) in the winter of 2015 after returning the other two to the university. Moreover, I recorded within a notebook all the work associated with data collection and analysis from the summer of 2015, as well as wrote down any personal reflections.

Locations of Camera Traps next to my House in Winter 2012 and Summer 2015

Two Coyote Pups Playing in the Wash

Bobcat (Lynx rufus)

The settings that I employed for my camera in the winter of 2015 included infrared picture mode with three consecutive images taken in a row when activated and an interval of three seconds between each set of photos. This was mostly the same as in the winter of 2012 with the difference being that no video mode was utilized. I once again used eight alkaline AA batteries and a two gigabyte SD card. As for time frame, the camera was placed outside on October 9, 2015 and taken down on January 2 of the following year (note: this resulted in a shorter study period than that of 2012 by nearly three weeks, when the camera had been set up on September 20). The data from the card was collected every five weeks. Finally, the location in which I put the device was 20 meters further south than the original site from three years earlier (see the satellite image above of the camera locations. The #2 camera corresponds with the spot I chose for the instrument in the winter of 2015). The rationale for this was that very few pictures were taken at the 2012 location in the summer of 2015. Thus, to ensure I would collect enough data in the winter of 2015, I set up my device at a slightly different spot that had photographed numerous species in the summer. Finally, my hypothesis was that the javelinas, coyotes, foxes, raccoons, and bobcats would show an overall decrease, while the rabbits wouldn’t be affected as much by the development.

Coyotes Chasing Fox

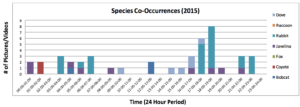

Before any kind of analyses could begin, image and video files had to be properly renamed and sorted. The program “ReNamer” was used to carry out the former step. The files were spontaneously relabeled based on the year, month, day, hour, minute, and second they were taken in. This was done to prevent any overwriting from occurring during the analysis. Next, each photo and recording was sorted into a specific folder based on the location it was taken at, what species were in the picture, and the number of individuals in the image. The next step involved using a program, written by Dr. Jim Sanderson, called “DataOrganize” to create two text files. The UTM coordinates, elevation, and start/stop dates of the camera were entered into one text file. The other had a list of all renamed pictures and videos. Finally, Dr. Sanderson’s other program, “DataAnalyze,” used these text files to create another text file with all the analysis numbers and information. These numbers were then entered into Excel spreadsheets where graphs and charts of the data could be created (note: for more specific information on analysis and using these programs, see my post, “Software,” under the “Tips and Hints” tab).

Taking a Dust Bath

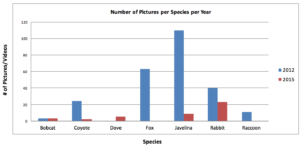

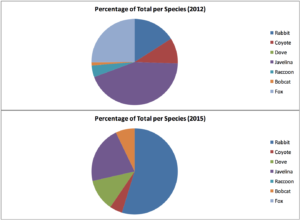

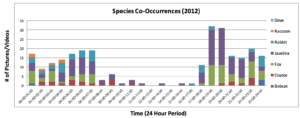

Overall, I captured a total of 1,177 photos/videos in the winter of 2012, and 151 photos in the winter of 2015 (note: these are images and recordings that contained animals; the ones that didn’t have any species on them, such as false triggers, were excluded from the analysis). Note the difference in scale for the last set of graphs.

The results indicate that the number of fox and javelina images decreased the most, whereas the change was not as drastic for the rabbits, raccoons, coyotes, and bobcat. First of all, the pair of foxes that had been frequently caught on camera earlier in 2012 was not seen at all in the winter of 2015, though one individual was photographed during the summer. In 2012, this canid was first captured on camera in mid-November both alone and as a pair. Ultimately, the species had a total of 63 independent pictures during the study period before any construction began (if a species is photographed more than once within an hour, those images are considered to be an “independent picture”). The javelinas also underwent a drastic decline. This animal was caught on camera 110 times in 2012, and only nine times in 2015. In addition, the number of individuals in the herd may have decreased. Originally, there were approximately 10-20 animals in one group based off of data and observations made during the day from a window. Now, the number of individuals most frequently seen together amounts to around five to ten.

The coyotes were caught on camera less as well, though the contrast between 2012 and 2015 was not quite as drastic as that of the javelinas or foxes (especially when considering again the shorter study period in 2015). Photographed once in 2015, they had by contrast been captured on camera 24 times in 2012. The coyotes were commonly observed living solitary lives, though occasionally two or three animals were spotted together. After construction began, the species was most commonly seen on camera with only one individual in the picture. Nonetheless, a pack of three to four animals had been noticed a few times that same winter.

Moreover, the raccoons, like the fox, were not caught on camera at all during the winter of 2015. They were photographed 11 times in 2012, commonly as a pair. However, during the summer of 2015, they were captured on camera three times (scat evidence was present as well). Additionally, the desert cottontail rabbits were photographed 40 times in 2012 and 23 times in 2015. Further, their young were often observed during the summer as that is the season when they reproduce. They were commonly spotted in groups of one to three individuals. Finally, the bobcat was caught on camera three times both years in the winter despite the fact that it isn’t frequently seen in the neighborhood. A pair was never noticed during the study periods, which may be explained by the fact that these cats live solitary lives.

Coyote Pair

Before discussing the above results, one point must be made clear: a few months’ worth of data is not very much to draw any large-scale conclusions. Often, these kinds of studies involve years of data collection and analysis. Thus, anything discussed here should be taken with a grain of salt and a very open mind. The second primary point that must be emphasized is the shorter study period in 2015 (around three weeks less). This will make the graphs appear more exaggerated than they actually should be.

One of the first questions that comes up is why the bobcat did not appear to be too affected by the development. One possible explanation is that they seem to do fine around humans, as is evident in that they have even been known to wander through cities. In addition, there were still numerous potential prey items around for the species, including ground squirrels, lizards, and rabbits. Nonetheless, it’s difficult to draw a conclusion here given how rarely the cat was photographed in the first place anyway. As for the rabbits, one would understand why this species wouldn’t be directly affected by a construction site taking place 500 feet away, considering they don’t need much room.

Raccoons and coyotes, like bobcats, have also been known to pass through cities and dwell in areas nearby. In the raccoons’ case, for example, the wall surrounding the development most likely wasn’t able to keep the animals out, considering their intelligence and abilities. In the long run, though, it is difficult to draw conclusions on this species considering that before any construction began, it was already rarely photographed or seen in the neighborhood. As for the coyotes, their pack numbers didn’t seem to have decreased. This could also be argued by the fact that during the summer of 2015, two young coyote pups were spotted in the wash. Therefore, the canids seem to still be reproducing in the area, even though the data states that they pass through the subdivision less often. Additionally, they too still have numerous potential prey animals to feed on.

While the data may suggest that several species weren’t too negatively affected by the urban development, it points to the fact that the javelinas were drastically influenced by this construction site. Besides photo evidence, this is further reinforced by the fact that neighbors noticed javelinas knocking over trash cans the day that the area to be developed was fenced off. This 15.14 acre piece of land was possibly one of the species’ primary feeding zones in the region. It should also be noted that javelinas need much room considering their large herd sizes. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that this removal of several acres of free land would have caused them to pass through the area less often in search of new feeding grounds. In addition, the gray fox was yet another species that seemed to have left the subdivision and moved on. Therefore, this animal didn’t appear to be quite as adaptable to urban settings as other species (such as raccoons, bobcats, and coyotes). The pair of gray foxes that was frequently caught on camera before any construction began may even have had its den on the piece of land that was rezoned, though this is speculation at best.

All in all, my hypothesis was partially correct. The prediction that I’d capture far fewer images of javelina and foxes, while rabbits wouldn’t be quite as affected, seemed to have an arguable basis. However, the coyotes, raccoons, and bobcat did not show as drastic a decline, especially when considering the shorter study period in 2015 and that the latter two species were initially caught on camera rarely anyway when compared to the javelinas and foxes.

Javelina Family

Upon reflecting back on this project two years later, there are definitely numerous things that come to mind that I would do differently next time. The first of these involves a longer study period to see if actual trends exist and perceived “trends” from the data aren’t just coincidences. Further, as mentioned earlier, the camera used in the study was set at a different location both years. Despite the minor 20 meter shift, the device was angled differently. Thus, animals that followed a certain route one year may not have been photographed another year, even if they took the same route. I’d therefore keep this consistent and include more cameras next time. A third key point to remember is that 2015 had fewer study days than 2012 (nearly three weeks less), which affects the reading of bar graphs since the difference of a species’ abundance between two years will look more exaggerated than it really is. That was human error; I had accidentally forgotten to set up the device when I should have. A fourth thought is placing cameras in various locations throughout the neighborhood as certain species may simply have changed travel routes. Finally, I wouldn’t throw down bait (one year had it while another didn’t), I’d keep the devices on the same mode for both study periods (i.e. either picture or video), and I’d be sure to collect the data from the SD card at identical time intervals.

As a couple final notes, I ended up giving two hour-long public presentations on my research. One was at the Dusenberry-River Library while the other was held at the Elmcroft Senior Living Community. I’d also attempted to give one at the Sabino Canyon Recreation Area, though it didn’t end up working out. Additionally, and hence the title of this post, my work once again landed me at the Southern Arizona Research, Science, and Engineering Fair (SARSEF) in March 2016. There I received numerous awards, including first place in Animal Sciences at the high school level, the Sky Island Naturalist Award from Sky Island Alliance, the Sonoran Desert Ecological Excellence Award from Saguaro National Park, the Biodiversity Award from the Center for Biological Diversity, the Wonder of Wildlife award from the International Wildlife Museum, and the Reid Park Zoological Society’s Outstanding Animal Project award. Finally, given my ranking at the regional fair, I was permitted to participate as well in the Arizona Science and Engineering Fair (AzSEF) a month later where I again placed first in Animal Sciences at the high school level.

Fox Rolling in the Dirt

All in all, I would say that this project was probably one of those “cherries on top” of my senior year in high school. Not only did it build up my résumé and provide me with a phenomenal learning experience, but it also let me meet some great people that I will likely be working with in the future (one of the judges who interviewed me at the fair now happens to be a good friend of mine). Moreover, the contacts I made in Dr. Culver and her database manager have greatly aided my brother too. He received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Computer Science at the University of Arizona, enjoys writing code, and is currently working with the same people I worked with to develop new camera trap analysis software. Ultimately, collecting random data my freshman year in high school really turned out to be one of the best decisions I made during my secondary education years. And with the second set of images I then collected as a senior, it took me to the science fair once again four years later. Who would have thought?