Sun Rising over the African Bush

From the time I was little it was always my dream to work in wildlife conservation, particularly with regard to big cats. Along those lines, I could see myself building a career abroad internationally since the animals I am interested in largely live on other continents, and because I have a passion for learning about other cultures. During the summer of 2018, that dream came one step closer to reality. In June I had the unbelievable privilege of interning with Wildlife ACT (Africa Conservation Team), an organization dedicated to the conservation of endangered species in various reserves in Zululand, a region located in the northern part of the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. For the first two weeks I aided in the monitoring of lions, leopards, rhinos, elephants, and other species through the use of camera traps, telemetry/radio collar equipment, and daily tracking in Tembe Elephant Park. For the second two I volunteered with Panthera, a big cat conservation organization with whom Wildlife ACT is partnered, in the Eastern Shores section of iSimangaliso Wetland Park by participating in the largest leopard camera trap survey in the world. From having some of the craziest encounters in the bush and experiencing some of the most breathtaking landscapes, to seeing some of the most exotic and beautiful animals and getting to work with some of the most amazing people, I can only say this is easily one of the best trips I have ever taken in addition to one of the best choices I’ve made in my undergraduate career. Not to mention it was great escaping the Arizonan summer and heading to the cooler African winter!

My Favorite: Camera Traps

There are hundreds of volunteer organizations related to wildlife in Africa. Many of them, unfortunately, are money-making scams that mask in the name of conservation yet are associated with exploitation. The primary reasons I chose Wildlife ACT over other programs I looked at, thus, are as follows:

1) The description of the work they do appealed to me (see below)

2) The program is dedicated to avoiding any physical contact with wildlife; hence I was assured I wouldn’t be lured into one related with a bad industry

3) The affiliates are well known (ex. such as Panthera; that was a big plus for me since I want to work with big cats)

4) Positive reviews online

5) It was one of the cheaper options

Even though the organization is young (founded in 2008) with a small staff of around 30 people, it quickly gained the respect of well-known institutions such as the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). It was additionally recognized as the Best for Habitat and Species Conservation in South Africa and the second best for the same award in all of Africa at the African Responsible Tourism Awards 2017. In short: if you are looking for a wildlife conservation volunteer program in which you will be participating in the active conservation of threatened and/or endangered species for a decent price and not simply going on a safari, this is the one.

Tembe Elephant Park

I ended up working as an intern for four weeks, and participated in two of their projects. The first was the Endangered Species Conservation Project, and the second was the Leopard Conservation Census. The Endangered Species Conservation Project works on five reserves: Tembe, Hluhluwe, iMfolozi, uMkhuze, and Manyoni. Each reserve accepts a maximum of five volunteers at a given time, and groups rotate every two weeks between parks. The Leopard Conservation Census works on said reserves in addition to the Eastern Shores section of iSimangaliso Wetland Park and several other areas. Nonetheless, they only perform their camera trap surveys at one location at a time, and then rotate every two months. For this one, my group was only composed of three people as opposed to five.

Enjoying the View

For my first two weeks with the Endangered Species Conservation Project, I was placed at Tembe Elephant Park. This reserve is known for its “tuskers,” or elephants with very long tusks, whereas the landscape is mostly bush with some open savannah-type plains. The actual work itself consisted of monitoring in the mornings and sometimes in the evenings that included working with telemetry equipment (i.e. radio collars), checking camera traps, and tracking by recording evidence of species of interest (ex. paw prints on trails). This was done both by hand and digitally with CyberTracker, a handheld GPS device for note-taking when out in the field. Date, location, time, GPS coordinates, species, and behavior, age, sex, and number of individuals were recorded in addition to any other points worth writing down. Morning excursions typically lasted from ~5 am to about 10 or 12 in the afternoon; evening sessions were shorter and more varied in terms of time with the average being 2-3 hours. Species we saw included lions, leopards, elephants, giraffes, zebra, impala, buffalo, nyala, and various kinds of birds. At this point I must add: there is nothing more thrilling than being surrounded by a group of curious young lionesses in the back of an open-air vehicle to start the day! Anyhow, in the afternoons we would also go on elephant monitoring sessions, though these excursions were more intended as a “break” for the volunteers since the park employee who took us on those did most of the work. All such data collection efforts serve to aid park officials in making management decisions. Information regarding population size, animal behavior, species movements, diet, injuries, inter- and intraspecific competition, genetics, and conflict with local communities may be useless at the moment but vital later on when deciding which individuals to translocate (relocate), which to breed, and where to focus anti-poaching efforts, among other matters.

Elephants at the Watering Hole

Don’t Get Too Close To Me!

And the Other (more peaceful!) Giant…Giraffes 🙂

Lilac-Breasted Roller and Red-Capped Robin-Chat

Spotted Eagle-Owl

Can You Spot the Leopard? (No Pun Intended!)

At camp, data sorting and entry into digital spreadsheets occurred approximately twice a week; camera trap photos were also tagged in the program Picasa based on the species present, view (ex. right/left side of the animal), age, sex, and individual i.d. if known. Lions, for example, can be identified based on the spot patterns of their whiskers. Moreover, some work back at camp could be unpleasant; this mainly had to do with picking up raw impala or nyala carcasses from the park’s butchery. We would tie them next to camera traps as a lure, or use them to feed animals in bomas (temporary holding enclosures). For example, Tembe had a pack of 14 African wild dogs in a boma while I was there. They had been temporarily confined due to conflict with local communities and hence needed to be fed every week. We even once went into the enclosure in the back of an open-air vehicle! Finally, after each long day, we were all typically in bed between 8 and 9 after finishing dinner. Overall, a “typical” day depended on the individual day and the respective projects that monitors were working on during that time.

At the Border to Mozambique

Mornings and Evenings are Gorgeous!

Lion roaring at dawn. If you listen closely, you can hear it echo across the plain.

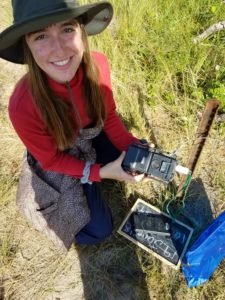

Working with Camera Traps and Telemetry Equipment

Getting Ready to Head Out

All About the People. Always.

I was also fortunate enough to participate in a translocation, one among several rarer events that do not occur frequently. These activities arise only when needed. During my stay at Tembe, the main goal was to remove four young lionesses from the reserve given that the area has had severe inbreeding problems in the past several years. As a volunteer, I was fortunate enough to witness the fruits of my efforts since the young subadults were finally tranquilized after several weeks without success. It felt unbelievable; the park rangers thanked us, the volunteers, because we had been the ones to help with data collection to track down these lionesses. In other words, we had actively helped in the conservation of the species and were not simply seen as “baggage.” The lions were eventually moved to Gorangosa Park in Mozambique, a country directly north of South Africa, where the animals had far more area to roam free. There were also future plans to bring in two new males to help establish a proper pride structure that was lacking during the time I was there. Overall, such experiences were a reminder that volunteering was not intended to be a safari like what tourists experience. Though thrilling, it highlighted the importance of responsibility; getting up early between ~4 and 5 every morning was the norm in addition to potentially having to leave camp unexpectedly at a moment’s notice. For example, Tembe has two camps, one in the northern part of the park and one in the south. The southern camp is the main one, though at one point we had to leave for the northern camp for the weekend as the lions we were monitoring resided there. The day after we returned south, we awoke to a note from our monitor at 5:00 in the morning telling us to be ready within an hour to head back up north again. Not only did this require packing our bags the day after we had come back, but it also required packing up all the remaining food we had left. Though such situations were slightly stressful, it was all 100% highly worth it.

Being inspected by several curious young lionesses…

…is quite an interesting way to start the day!

An Intrigued Subadult

Getting Surrounded by Some Big Cats

Three Sisters Playing Together

Monitoring efforts paid off and these tranquilized lionesses will be relocated to another park

During my second two weeks I worked on the Leopard Conservation Census sponsored by Panthera at Eastern Shores, iSimangaliso Wetland Park. The diversity of ecosystems here is incredible and far richer than at Tembe, ranging from savannah and Bornean-type forest, to marshland and the beach. This one was strictly focused on camera trapping; Panthera uses their own camera traps that do not use SD cards and instead download data directly onto a USB. There are a total of 41 sites at Eastern Shores with two cameras at each one placed parallel to one another. A typical day consisted of leaving camp at 7:00 am to check the devices by collecting the data/changing the batteries and returning at around 11 or 12 in the afternoon. The rest of the day was then dedicated to sorting thousands of photos based on species and location number and identifying individual leopards from spot patterns. Panthera also has a program, HotSpotter, that automatically compares such patterns, though volunteers still do the work by hand in case errors occur and to create a backup. Approximately two days of the week were dedicated to such data work as opposed to heading out into the field. Overall, the project had far less diversity of activities than at Tembe and more free time which typically consisted of heading to the beach (5 minute drive away) and chasing off curious monkeys that showed a little too much interest in the kitchen. There was additionally a group of students studying whales with a marine organization nearby (also a 5 minute drive away), resulting in some communal, festive evenings. Their house had better signal than our residence too, so you can imagine at who’s place we liked to hang out in our spare time!

Having Fun Out in the Field and Indoors

Another leopard spotting game! We saw this female on our first day on the way into camp!

Exotic frogs and flowers. The three reed frogs on the left were sitting behind the camera trap

Monkey Chilling on the Beach and Right Outside our Front Door

Zebra and Kudu

While general priority species such as elephant, rhino, hippo, hyena, various kinds of antelope, and others are important to monitor so that park managers can watch their numbers, Panthera has other interests as they conduct these surveys to obtain an estimate of leopard density to ensure populations remain stable and take action if not. Tracking individual cats is not as important since the animals by nature enter and leave reserves freely despite the presence or absence of a fence, so the only time monitoring a particular leopard would be vital is in the case of an injury or snare, such as from a poacher. Even then, however, finding the animal would be difficult in a region as large as iSimangaliso. Radio collars are additionally a big no-no with these predators since weight fluctuations tend to be common. Moreover, it’s worth mentioning that Panthera has a citizen science project that can be accessed here where thousands of volunteers help identify species in camera trap photos online from all over the world. Such work is needed as it allows managers to determine both if populations are stable and if their habitats are ecologically healthy and biodiverse.

Enjoying the Diversity of Ecosystems at iSimangaliso

A Day at the Office

At the Beach

View of the Ocean and the Park

My Happy Place ❤️

iSimangaliso Wetland Park: Also Known as “Place of Wonder”

My volunteer group also spent a 3 day “mini vacation” in nearby St. Lucia our second week which consisted of horseback riding, a hippo and crocodile tour, a Zulu cultural tour, souvenir shopping, and eating out in some nice restaurants. I must add it felt quite odd becoming a tourist for those couple days!

At a Local Zulu Market and Enjoying the Reserve on Horseback

Taking a Horseback Ride

Hippo and Crocodile Tour!

Watching a Zulu Dance and Showing the Children Some Photos on my Phone

Always About the Camera Traps…

…And the People Of Course😉

To conclude, it’s definitely worth giving a huge shout-out to the phenomenal monitors and staff of Wildlife ACT. First off, it was rewarding witnessing local involvement; one of the women employed by Tembe Elephant Park who accompanied us on monitoring sessions was of the Zulu people and desired to pass her love of wildlife onto her children. As for monitors employed by Wildlife ACT, there are only a total of 12, two per project (stationed at the five reserves of the Endangered Species Conservation Project in addition to the two working with the leopard census). Because of the small group sizes, I got much personal attention from my supervisor(s). They knew I was an intern and therefore took the extra time to teach me and answer any questions I had since I want to go into wildlife conservation as a career. Along those lines, I also registered for internship credit with my university; attached below are two papers I wrote accordingly. The first, written for Wildlife ACT, is short (3 pages), whereas the second for my university is a longer research report (12 pages). Both pertain to the translocation of mammals given my experience with the lions at Tembe.

Wildlife ACT – Translocation of Large Carnivores at Tembe Elephant Park

Translocations in Conservation: Techniques and Effectiveness

That all being said, I can only wonder at how the Lord has blessed me and dream of the day I’ll go back as I’ve left a piece of my heart behind in this place of wonder I grew to love so quickly. The quote at the bottom of this post sums it up perfectly.

Logo on the Side of the Field Truck

Finally, if you would be interested in volunteering with Wildlife ACT, you can find my full review with both pros and cons at GoOverseas.com. It’s similar to what I’ve written here with added details on accommodations and other practical matters in addition to a short list of pros and cons.

Sunset at Lake St. Lucia

“Africa changes you forever, like nowhere on earth. Once you have been there, you will never be the same. But how do you begin to describe its magic to someone who has never felt it? How can you explain the fascination of this vast, dusty continent, whose oldest roads are elephant paths?” – Brian Jackman