Wildlife species all around the world face a variety of threats, including from illegal hunting, or poaching. Poaching can be incentivized by a variety of factors, including to obtain trophies, capture bushmeat as food, or derive animal products for purported medicinal purposes. Wire snaring is one of the most commonly used forms of poaching in the world, particularly in the Global South. A snare is composed of a wire or cable in the form of a noose, either on the ground or suspended in the air. When an animal walks through the noose, the wire constricts and the individual is caught. Many animals die in snares, while others break free and are permanently injured. Although ungulates (e.g., buffalo, antelope, gazelle) are usually the primary targets of snaring, a variety of species, including those that are threatened or endangered, can become tangled in snares and get injured or perish.

The lethal impacts of snaring are being increasingly measured (i.e., how many animals of a given species die from being captured in snares). However, we know less about how snaring, and poaching more generally, can impact wildlife species in a non-lethal manner. We can reasonably expect that an injury from a snare will affect an animal’s behavior, health, reproduction, or survival. Moreover, wildlife might alter their behavior in advance of being caught in a snare to reduce their likelihood of encountering one. Such changes in behavior can then come with tradeoffs that affect nutritional intake and stress levels. If enough individuals in a given population therefore experience non-lethal snare injuries, or display changes in their behavior or fitness to avoid being captured in snares, the effects could actually manifest at the population level because of lowered reproduction and survival.

The focus of my dissertation is therefore to assess whether these non-lethal effects of wire snare poaching exist in the African lion. My supervisor is Dr. Robert Montgomery at the University of Oxford. Our study site is in Murchison Falls National Park, Uganda, which hosts the most powerful waterfall in the world, formed by the Nile River. The park however also experiences some of the highest densities of snares documented anywhere in the world, as impoverished communities nearby attempt to harvest ungulates for food. Lions are therefore not targeted by poachers in this park, but are frequently caught in snares nevertheless. In particular, there are two questions I am focusing on:

1) Does wire snare poaching impact lion body condition (nutritional status)?

2) Does wire snare poaching impact lion population density?

Moreover, I am interested in determining how wildlife respond to human hunting more generally. Do they indeed recognize a human threat when they see one? Do they react? These cues of hunting could come in various forms, like visually seeing a hunter or hunter’s trap, or hearing sounds of hunting like gunshots. If we have evidence that animals do indeed recognize and respond to potential threats, it will further help link wire snare poaching to any changes we detect in lion body condition or population density in Murchison Falls National Park. Thus, I am assessing how wildlife respond to human hunting using two methods:

3) Setting motion-activated camera traps next to dummy (fake) snares and watching animals on video to see whether and how they react

4) Conducting a literature review to summarize our existing knowledge from prior studies

My literature review has already been published. Here is the link.

I was also able to present my proposed research at The Wildlife Society conference in 2024, as part of a symposium and panel discussion on international human-wildlife coexistence.

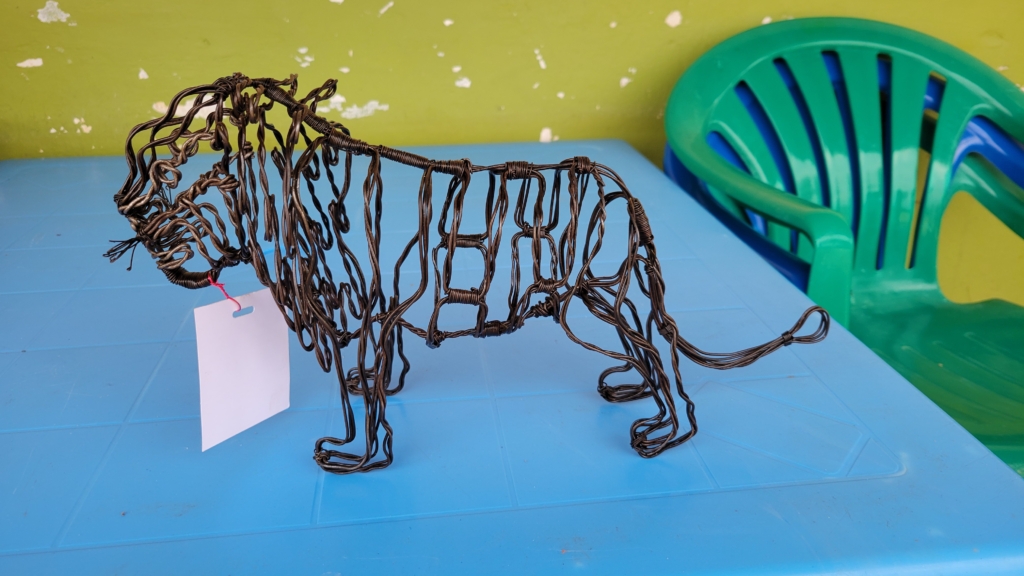

The findings of this work will ultimately be shared with Uganda Wildlife Authority, the government agency responsible for managing wildlife in Uganda. Funding for this project is provided by a multi-year grant from UK Research and Innovation, as well as a smaller grant of over 17,500 Australian dollars I personally received from the Taronga Foundation. Worth mentioning too is that this research is being conducted in collaboration with two Ugandan-registered NGOs: the “Innovation for Conservation” (ICON) and “Snares to Wares.” ICON provides employment opportunities to Ugandan locals in conservation practice and research, an initiative I participate in by training my research assistants how to collect the data I need. Snares to Wares, in turn, is a project of ICON that trains and employs artisans from the communities surrounding the park. These individuals take the snares that are removed by the government and craft sculptures of wildlife out of them; the sculptures are then sold in nearby tourist lodges and globally. The revenue generated from these activities thus provides an alternative source of income to individuals who might be susceptible to engaging in poaching themselves.